The surface of the Sun

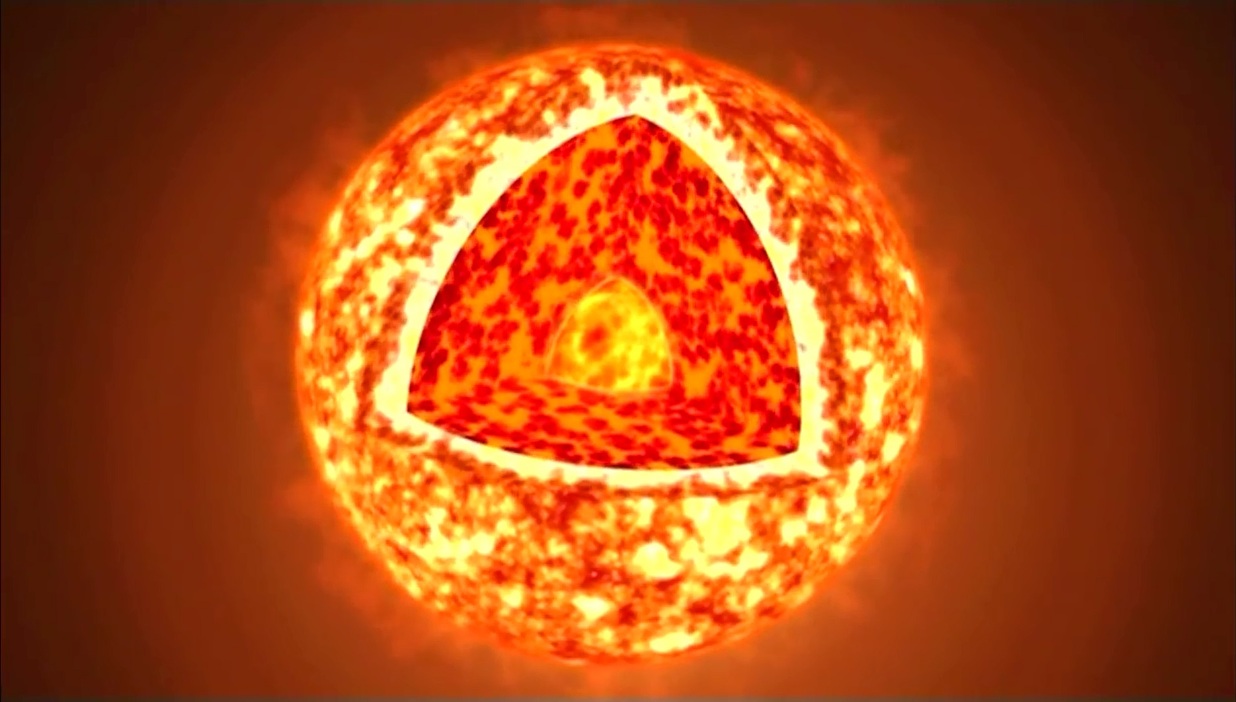

Despite being five million degrees Celsius at its surface, or nine million degrees Fahrenheit, the power generation density at the core of our Sun is the same as a garden compost heap. Or, in human terms, about that of your own metabolism. But the Sun is definitely no compost heap, or a human either. Its sheer size and scale allows it to ramp up to its nuclear furnace to fantastic temperatures and, in doing so, provide all of the energy that sustains life on Earth. At its helium and hydrogen core our Sun generates constant and phenomenal fusion power, and is even hotter. Super-hot ionised gas plasma thirty times denser than rock, at thirty billion tons per square metre pressure, churns at fifteen million degrees Celsius.

Because we’re us, the amazing human race, of course we like to think our Sun is unique. But although it’s the only star known to host habitable planets, currently known that is, most astronomers say that our Sun is fairly ordinary and nothing special. They say, in reality, it’s just one of your typical yellow dwarf solar-type stars, and one of many hundreds of billions that are around in the broad universe. The trouble is, it’s the only star that the nine billion different species across the Earth’s ground and seas rely on, every day, to enable us to live.

Sitting at the precise centre of our Sun, a single photon was vibrating wildly. At the Sun’s core this photon had been created as a very, very small part of three hundred million tons of hydrogen being converted into helium nuclei every single second. It was exactly the same type of photon that had given Earth its light, warmth and fuel for growth for 4.6 billion years, give or take a year. Despite the high temperatures at the Sun’s heart this small photon was moving very slowly, at thirty inches an hour, and still had half a million miles to go until it eventually reached the surface of our star.

Our photon needed to travel through the sun’s radiative zones, its convection zone and finally the outer photosphere, where most of our star’s immense power comes from. So this event certainly wasn’t happening today. In fact our photon’s long journey started long ago in the prehistory of Homo sapiens, just as man was about to leave the African continent and begin to migrate into Europe.

Jump forward from 170,000 years ago to right now, this very morning, and our solitary photon finally reached our Sun’s surface. Here, it combined with x-rays and ultraviolet radiation into a growing, glowing sunspot group, roiling at five million degrees Celsius. At the sun’s edge, titanic magnetic forces accelerated minute primordial cosmic particles up through the superheated plasma, into a sigmoid coil, creating an enormous glowing bright white arch, bulging at the sides. Colossal curved magnetic lines of force flowed out from the sun into space, sending the hot plasma and photons rapidly out and then violently back in a series of loops, each high coil standing one hundred thousand miles high at its dizzying peak, forty times Earth’s diameter.

A gargantuan helix of magnetic force, the biggest created in human memory, was suddenly released from the huge magnetic influence of the Sun. Sited just west of the rotating centre, trillions upon trillions of tons of matter and hot plasma were expelled straight off the surface of the Sun, out into the empty firmament. This violent energy pulse, blasted out directly from our Sun, is called a Coronal Mass Ejection, or CME. Containing almost uncountable numbers of electrons, ions, atoms, and light photons, this gigantic bulb shaped plume of high energy particles, gamma rays, x-rays and massive magnetic fields, was pumped out into interstellar space at ten million kilometres an hour.

500 seconds later the first titanic batch of energy from the Pulse hit the Earth.